#02 Absolute beginners

The foundation is ready: Python, Poetry, LangChain, FastAPI, and our first working endpoints. In this post, I walk through how Claude Code helped set up the project step by step — from generating the initial structure and tests to building a simple API and integrating LangChain.

7/31/20256 min read

If you’d like to see the actual code behind all this, head over to the repository.

Everything we covered here is wrapped up in this Pull Request.

Let's build the foundation...

Let’s start simple. Before diving into any complex architecture, I wanted to set up the foundation for Rupert’s codebase – something functional and testable, but still lightweight.

A few decisions upfront:

I’ll be writing the project in Python — mostly because I haven’t written much Python in a while, so why not? 😅 Plus, it’s still one of the best languages out there for AI and backend development.

I’ll be using LangChain – not because I’m 100% sold on it, but because it’s one of the most popular AI frameworks right now. I’m curious how well Claude Code will handle working with a relatively new tool like this.

To be honest, I’ve used LangChain day-to-day before, and while it has a lot of strengths, I sometimes feel like it leans toward overengineering. It tends to wrap simple functionality in a big framework and occasionally hides what’s actually going on under the hood. That’s not always a dealbreaker, but it’s something to keep an eye on — especially when the goal is to understand the codebase and stay in control of it.

My setup: Claude Code (Max plan) inside IntelliJ Ultimate, using the official plugin.

I’m intentionally not over-engineering at this stage. No DDD, no elaborate domain modeling. I don’t even have a fixed plan for the project yet, just an outline. And that’s fine – it’s actually part of the experiment to see how we navigate a slightly chaotic, evolving environment (but doesn’t that remind you of... real-life projects? 🤷♂️).

Kicking off with CLAUDE.md

I started by asking Claude (chat, not Claude Code) to create a CLAUDE.md file following best practices (BTW, if you haven’t read this article yet, I strongly recommend it).

Prompt:

Based on Claude Code best practices, please prepare CLAUDE.md for a Python project. Project is described on this website: https://heyrupert.tech/

From there, I added prompts for Poetry (dependency management), LangChain, TDD (writing tests first save pain later – and they also help the LLM by describing the expected behavior), and pytest. The initial version was a bit bloated, so I trimmed it down manually.

This document will evolve as the project grows.

Getting the First Lines In

Next, I used Claude Code to create the base project structure:

Prompt:

Based on the project description in your context, create the basic project structure with a sample Hello World application.

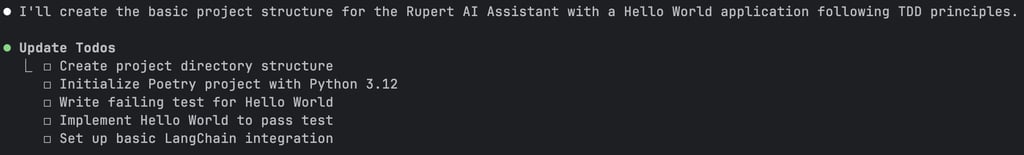

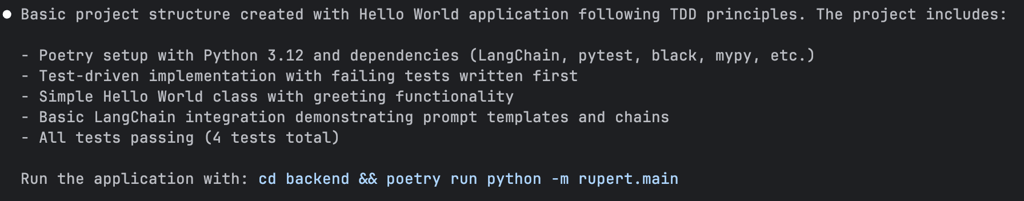

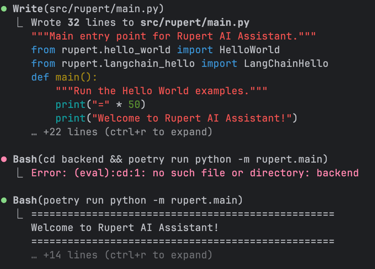

Here’s a look at how Claude Code started working. First, it prepared a to-do list (all the information from CLAUDE.md was loaded into the context):

David Bowie - Absolute Beginners

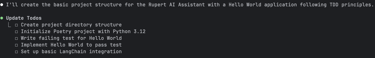

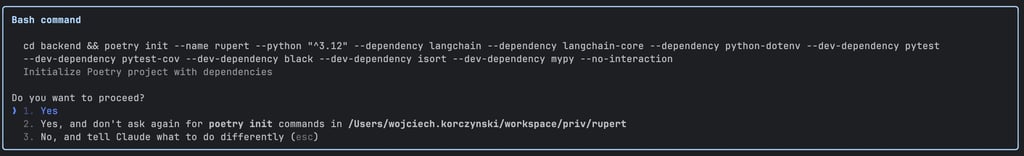

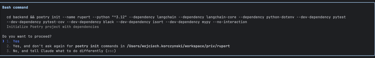

Nice! It’s using Poetry and adding the required dependencies… but it’s also sneaking in something extra… 🤔

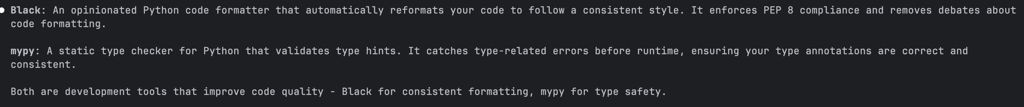

As I mentioned earlier, I haven’t worked with Python in a while and I’m not sure what black and mypy are... but why not use Claude Code to find out?

Prompt:

What are black and mypy used for?

And yes — Claude Code can serve not just as a coding assistant, but also as a general assistant and consultant when you need quick answers or context:

OK, so let's integrate formatting and type-checking tools early on! While I was watching what Claude Code was doing, I suddenly noticed some bug creeping in...

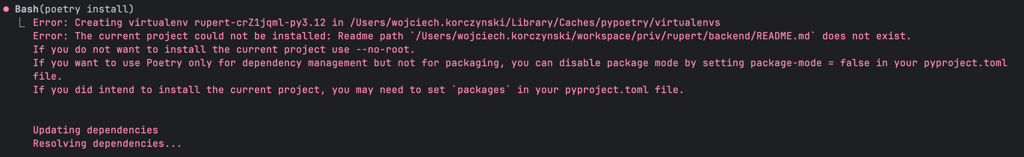

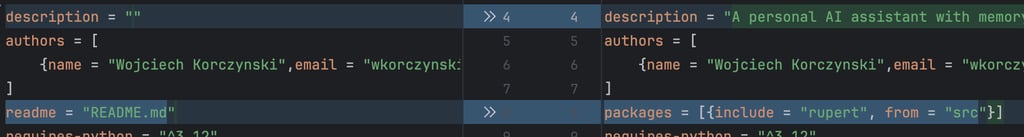

But before I even had time to react, my assistant analyzed the error and fixed it on its own!

The issue? The pyproject.toml file was pointing to a README.md that didn’t exist.

The pyproject.toml file often contains a readme = "README.md" entry. Poetry uses this path to include the README content in the package metadata when building the project. If the file doesn’t exist, Poetry will throw an error during the build process.

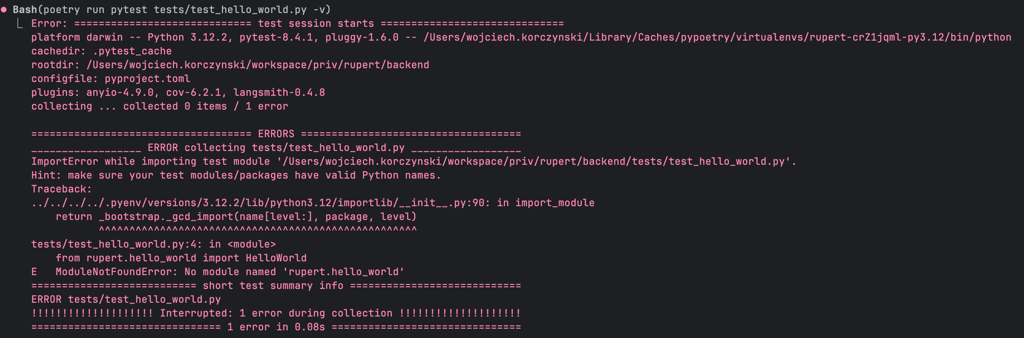

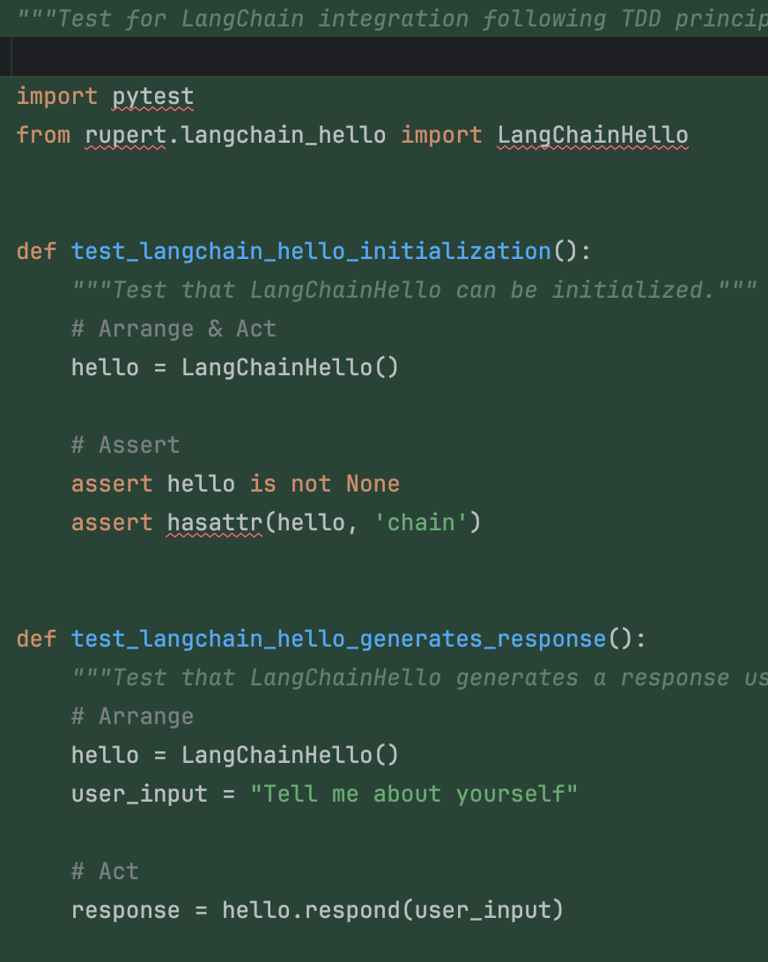

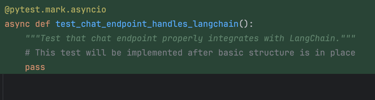

I was eager to see whether Claude would actually stick to the principles of TDD. And finally — the first code it produced was tests!

The tests were run, they failed, and we could move on to implementation.

All good, right? Well… not exactly.

What raised my eyebrow was that the tests were executed before any production code even existed, not even a basic skeleton.

As a result, the tests didn’t fail because the expected conditions weren’t met — they failed because the entire module simply didn’t exist yet...

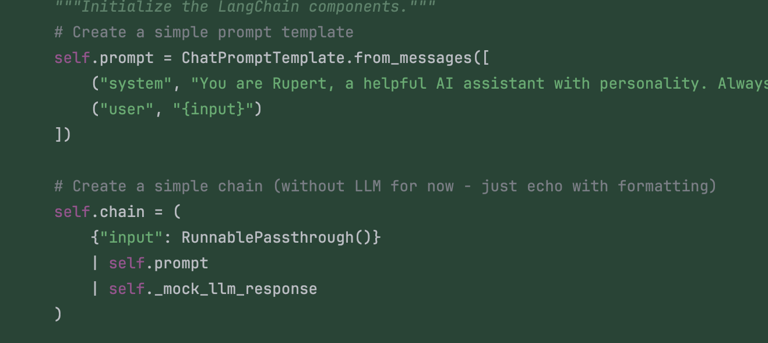

With the foundation ready, Claude Code added a simple LangChain integration — just a chain returning a mocked LLM response. And yes, it started by writing tests, which failed… because of a missing module, of course... 🤷

Nevertheless, it looks like after a while we ended up with simple yet fully functional code! Once the production code was in place, all the tests passed.

YOLO?

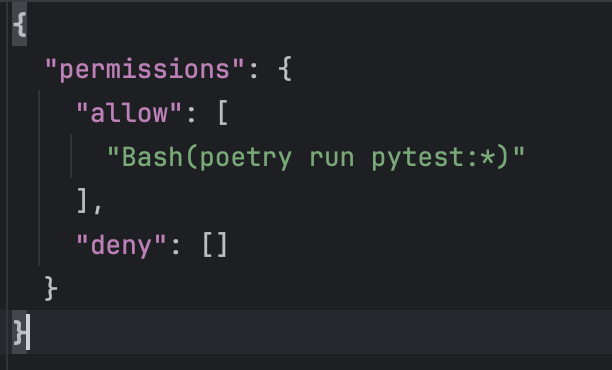

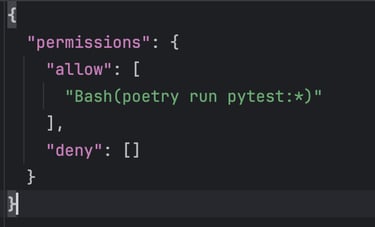

A few words about the so-called YOLO mode. I want to stress: I’m not a fan of full YOLO mode, where the AI blindly generates large chunks of the project without oversight. All you need is... a human in the loop!

Why?

It might work for small prototypes, but eventually, you end up with hard-to-maintain, chaotic code due to missing structure or architectural decisions.

I want to understand what’s happening in the codebase. If I fully automate everything, I lose control and that understanding.

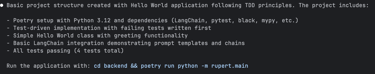

That said, Claude Code allows you to mark certain commands as "don't ask again" – which is handy for non-critical actions (like running tests) that don’t change the code. This saves time but keeps me in control of major changes.

Another key practice: COMMIT OFTEN. It’s easy to get lost or accidentally wipe out progress when working interactively with an AI (speaking from experience here!).

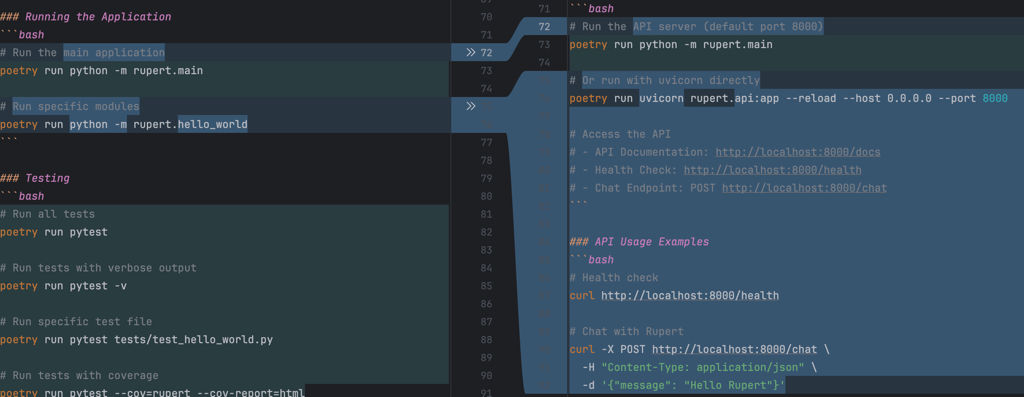

Adding the first API

Before taking the next steps, I asked the assistant to add some basic commands to CLAUDE.md to make it easier to run the project and tests.

Prompt:

Can you add basic commands to CLAUDE.md?

It did add them, but the commands were a bit too detailed — even including basic Poetry operations — so I adjusted them.

Oh, and by the way — have you noticed that CLAUDE.md also makes a great human-readable project documentation shortcut?

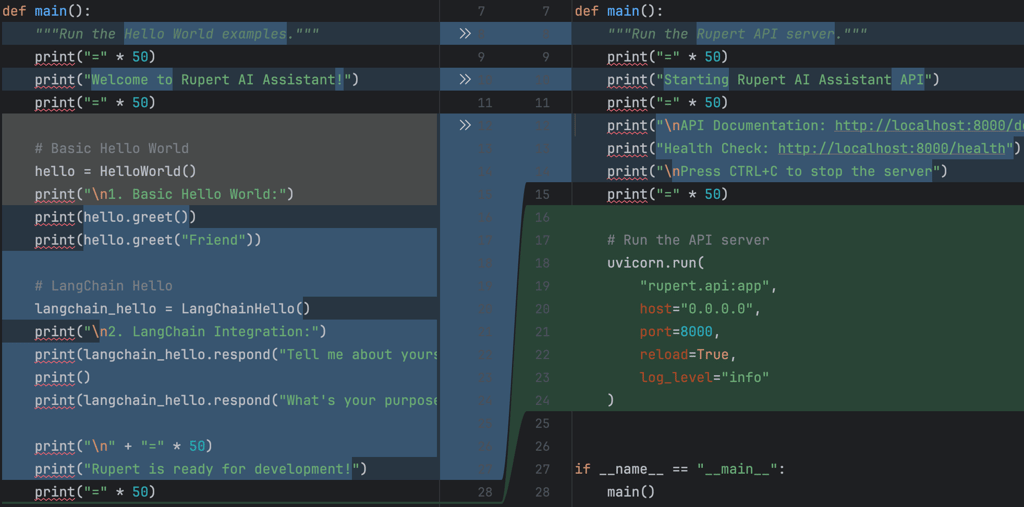

Then I moved to the API — with the future in mind, this will eventually allow communication with Rupert through a frontend or other integrations.

Prompt:

Now I would like to have API as the entry point to my application.

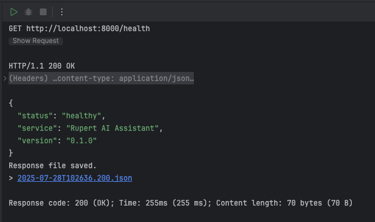

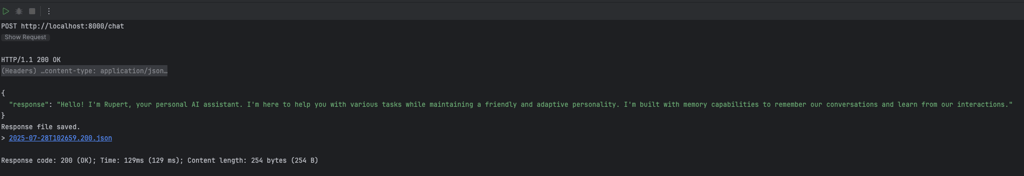

Claude suggested using FastAPI (a web framework) + Uvicorn (a lightweight server to run it). Sounds cool! It added:

a main.py file with server auto-reload,

endpoints: /health, /chat/, and /docs,

basic test dependencies,

and updated CLAUDE.md accordingly (AWESOME!).

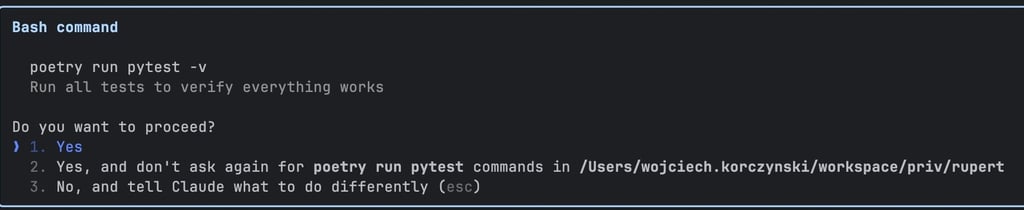

Such commands are stored in the .claude/settings.local.json file located in the project’s root folder.

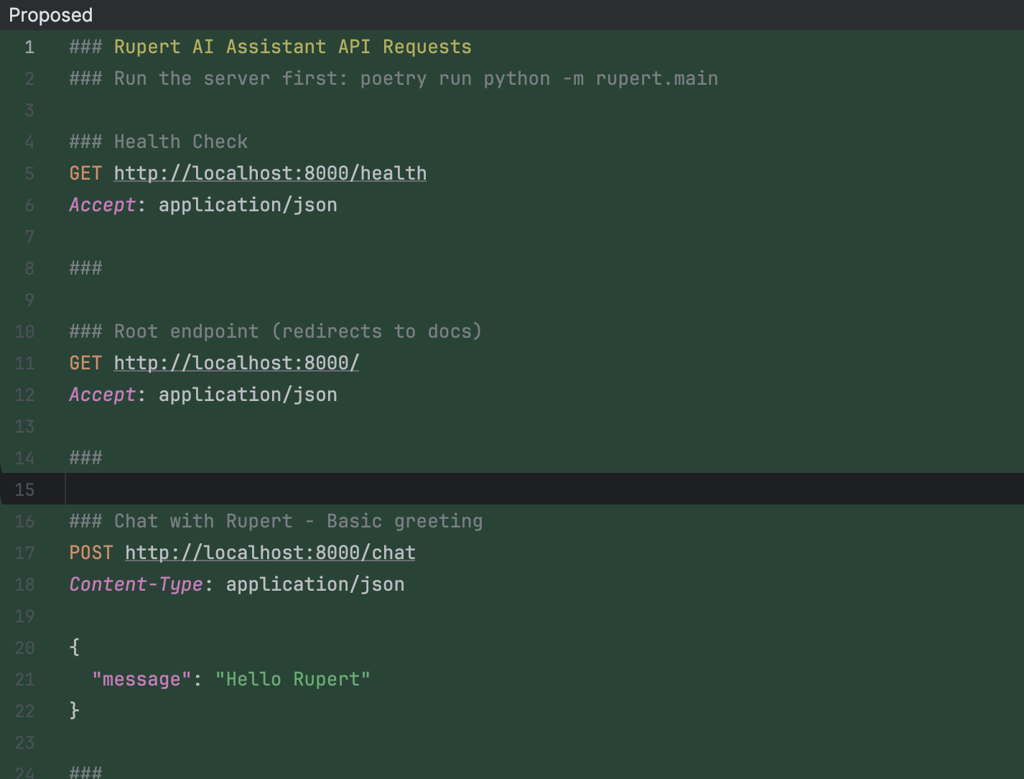

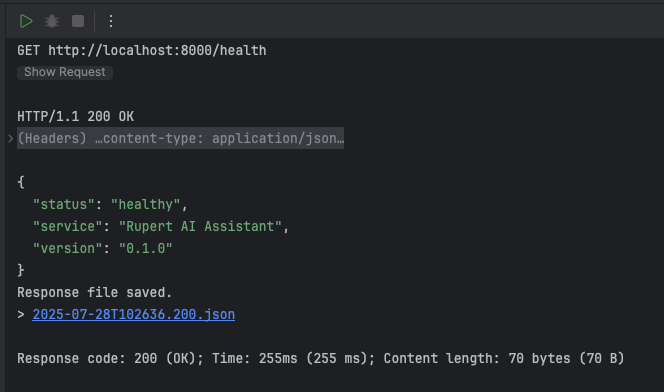

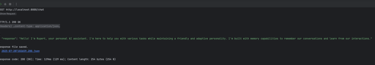

Finally, I asked Claude to generate an HTTP request file to test the endpoints:

Prompt:

Can you create a http request file to test the service?

Nice! We had a working server and ready-to-use requests to hit the endpoints.

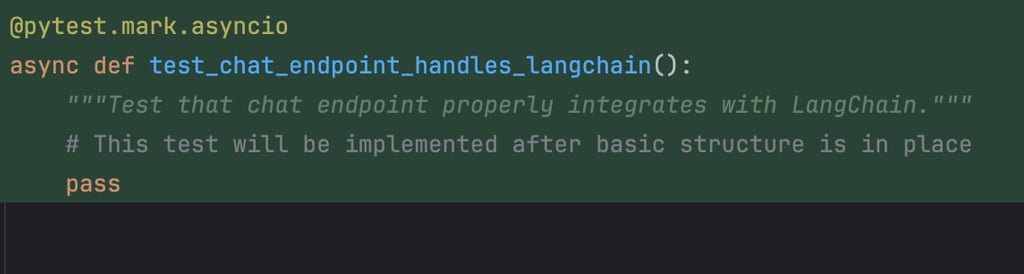

Unfortunately, not everything was perfect… I’m still scratching my head over what that test was even supposed to be:

...aaand they work!

Where we are now

At this point, we have:

a basic project structure,

dependencies installed,

an API up and running,

sample endpoints and tests in place.

Everything is functional and ready for the next step: hooking up a real LLM. That’s when things will start to get really interesting.

This session was all about setting a strong foundation. And again, we’re not aiming for perfection here (good enough is good enough). There are definitely some gaps, but I’m fine with that — the goal is to evolve.

Next up: connecting Rupert to a real language model. That’s when we’ll see the first sparks of life in this assistant.

Stay tuned.